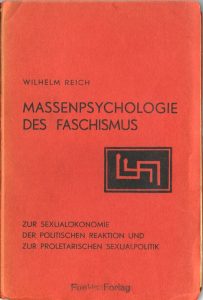

After eighty-seven years, the original 1933 edition of Wilhelm Reich’s Mass Psychology of Fascism is published for the first time in its original form

Andreas Peglau

“Society must be in resistance to us, for we behave critically towards it; we prove to society that it is in large part itself the cause of neuroses.” (Sigmund Freud, 1910).

To be consistent, psychoanalysis, both as a social science and as a therapeutic method, must be critical of society. Given this, the original version of Wilhelm Reich’s Mass Psychology of Fascism, published in the late summer of 1933, can be regarded as one of the most important psychoanalytic books ever written. More particularly, Reich’s book was the first text to address the psychosocial underpinnings of the Nazi system, working in a field now referred to as right-wing extremism studies.

Nonetheless, the book’s first edition has been almost completely forgotten, only available in pirate editions or at high prices from antiquarian bookstores. Existing references to Mass Psychology of Fascism almost always mean the 1946 English-language third edition, which has been available in German since 1971. But this edition differs radically from the original version of the book.

An independent work

In 1933 Reich was still writing as a “leftist” psychoanalyst, a critical ally of Freud. His declared aim was to fuse elements of psychoanalysis and Marxism in order to create something new, which he called “sexual economy.”

Reich had lived in Berlin since 1930, and his book was written as a direct response to the sharp rightward lurch of politics in those years. Reich worked against to the rise of right-wing politics in several ways, in particular as a sexual reformer and an active member of the German Communist Party. His experience of that moment, and the insights he gained, are recorded in Mass Psychology.

The 1933 book is thus also an eyewitness account, in which a Marxist psychoanalyst of Jewish origin analyzes the fall of Weimar and the Nazi victory, based on direct experience and observation. In addition to this, the book also brings to light the psychosocial characteristics of international fascism.

Reich was unable to complete the book until arriving in Denmark, his first country of exile, in May 1933. In the same year he was expelled from the German Communist party and from international psychoanalytic organizations.

By the time Reich set about revising Mass Psychology of Fascism in 1942, he had already been living in the United States for three years. The general circumstances of his life had radically changed, and so had his understanding of his own work, in both scientific and political terms.

By now, Reich had distanced himself from Freud and Marx, and even more firmly from any kind of party politics. He now categorized Stalinism as a “red” variety of fascism. In December 1941, he was arrested by the FBI – in part because of his past involvement with communism in Europe – and imprisoned as a “dangerous enemy alien.” He was released the following month after several weeks in prison. As well as its political change, Reich’s work also had a new scientific focus: his research into the life energy which he called “orgone.”

All of this was clearly reflected in the content and vocabulary of the third edition, not to mention in its sheer size. The book had more than doubled in length, thanks to the insertion of six texts written between 1935 and 1945. Valuable as these additions were, they included significant new developments in Reich’s thought, seriously harming the book’s overall coherence.

The additions entirely eliminated the immediacy of the book’s first version. Thirteen years after the original publication, Reich’s understandable efforts to make more broadly valid arguments came at the expense of the book’s former accuracy. By now, he was striving to come up with formulations which could apply to all authoritarian, despotic, and patriarchal systems, and which would in particular include Stalinism. But many of his new formulations failed to pin down capitalism, the Weimar Republic, and the National Socialist movement with the same precision as the 1933 edition.

The 1946 third edition of Mass Psychology undoubtedly represents an important development in Reich’s work, remarkable in its own way. But it is no substitute for reading the original.

Suppressed rather than used

From around 1933 on, socially-critical tendencies within psychoanalysis were permanently undermined, first by the assimilation of German psychoanalytic institutions to the Nazi regime, and second by the medicalization of Freud’s teachings in the United States around the same time. To this day, no psychoanalytic work – with the exception of Erich Fromm’s 1973 Anatomy of Human Destructiveness – has analyzed the psychosocial roots of fascist tendencies and right-wing movements with anything like Reich’s thoroughness in Mass Psychology.

Despite this, most of mainstream psychoanalysis continues to ignore, defame and marginalize Reich. His entire work of social criticism plays almost no role in the field, and one may search in vain for any adequate discussion of Mass Psychology.

More remarkably still, Reich’s book is very rarely mentioned in contemporary research into authoritarianism, fascism, the Holocaust, Nazi perpetrators, and right-wing extremism. The omission is all the more striking since currently accepted definitions of “right-wing extremism” correspond very closely to Reich’s conception of fascism as being authoritarian, nationalistic, militant, and racist (above all antisemitic), in addition to its glorification of (male) violence.

This blind spot toward Reich is all the more unfortunate since his work also introduced other key insights into the nature of fascism. These include the mutual dependence of leaders and followers, and the role played in the emergence of the extreme right by religions which are hostile to desire and the body and repressive towards children, women and sexuality. In short, it insists on the role of the patriarchy, and of authoritarian forms of socialization which suppress sexuality and the emotions, but are regarded as “entirely normal.” Only this kind of socialization could turn psychologically relatively healthy infants into docile subjects, into racists, into fanatics with a will to destruction. In other words, into potential fascists.

Many contemporary studies of fascism could benefit from a close reading of Reich, since they rarely come up with good answers to two crucial questions. First, what psychological state was required for people to actively participate in destructive movements like National Socialism, and even the Holocaust. Second, how was this mental condition brought about?

Reich’s continued relevance

The 1933 edition of Mass Psychology of Fascism has never been “outdated.” But its relevance has rarely been as pressing, given the political shift to the right currently under way in Europe and beyond.

For all the reasons given above, republication of the book was very much needed. In January 2020, Psychosozial-Verlag Gießen made the original German text available again, in an edition including extensive biographical and historical appendices.

An English translation is currently in preparation, to be published in 2024-5 by Verso, the largest independent radical publisher in the English-speaking world.

***

Here you can download the above text as pdf.