by Andreas Peglau[1]

For a better understanding of this text and what Reich called „Sexpol“, it is recommended to read in advance The Unified Associations for Proletarian Sexual Reform and Maternity Protection and Wilhelm Reich’s real role in the German „Sex-pol“

*

Already during his lifetime Reich was the victim of intense slanders. They never stopped. Peter Bahnen has the merit of being the first to reconstruct Reich’s sexual reform activities in Berlin. However, this was done on the basis of a clearly negative bias against Reich. Bahnen also doubted Reich’s figures about the „German Sex-pol“.

Reich (1934, p. 263) had reported that the first congress of a „Einheitsverband für Proletarische Sexualreform und Mutterschutz“ (Unity Association for Proletarian Sexual Reform and Maternity Protection, UA) „captured some 20,000 members in one fell swoop“. He later became more specific, writing that the first UA congress „captured about 20,000 members in a total of about eight associations“ (Reich 1995, p. 164). In the course of a year, „unified organizations were also formed in Leipzig, Dresden, Stettin, etc.“ – by which Reich may have been referring to the further foundations of UAs or of local UA associations. The „movement,“ Reich continues, „spread rapidly“: „Within a few months it had already doubled in size, to about 40,000 members“ (ibid.).

Bahnen comments, the

„tendency to exaggerate and dramatize everything, which is expressed in Reich’s liberal use of figures, in conjunction with the […] urge, bordering on the delusional, to inflate the size and importance of one’s own knowledge, is particularly noticeable in statements about his organizations“ (Bahnen 1986, pp. 86f.).

In a later article, Bahnen was even quite specific by suggesting that the UA

„remained a small splinter group with about 3000 members. All higher figures […] lack any basis and are an expression of those fantasies of grandeur that Reich published in his autobiographical writings“ (Bahnen 1988, p. 8).

Marc Rackelmann also searched in vain for evidence for the figures given by Reich and therefore considered it possible that Reich exaggerated here. Rackelmann estimated the real size of the UA – he as well as Bahnen did not elicit the existence of several UAs – „at least in 1931“ to be „well below 10,000“ (Rackelmann 1992, p. 54). He gave a conclusive reason for this: Since there is evidence that only 8,500 copies of the association’s journal Die Warte were printed in August 1931, there could hardly have been more than 8,500 members at that time – since every member was surely supposed to receive a copy.

Also since the fundamental credibility of Reich is at stake here, I thought it worthwhile to compile what facts I could find about it in several archives and publications. Unfortunately, when I present these in the following, accumulations of figures cannot be avoided.

Title page of „Liebe verboten“ (edited copy, color in original not known)

On the German sexual reform movement as a whole, there are partly consistent, partly contradictory figures.

The brochure Liebe verboten speaks of 300,000 members of the sexual reform and birth control associations.

Reich (1995, p. 163) certainly had this group of people in mind when he wrote:

„Germany in 1930 comprised about eighty differently structured, separately run, and often mutually hostile sexual-political organizations with a total of about 350,000 members.“

A police report of 13.4.1931 reveals the assessment: „In Germany, such [sexual] organizations exist in all districts, springing up like mushrooms and having in their ranks hundreds of thousands of members. In Berlin, the organization counts about 70,000 members.“

In Liebe verboten, the members of the pure sex reform associations (i.e., not including the birth control associations) in all of Germany are again separately given as 150,000. This figure is also given in a police report of 15.8.1931 and other sources.

In a 1932 article, the sex reformer Hans Lehfeldt refers to „about 113,000“ total members given by the associations, but adds:

„The actual number, however, is considerably higher, once because several splinter organizations have been left out of account, but above all because in the case of some associations the wives of the members, who are often particularly active in the movement, are probably not taken into account.“

Lehfeldt’s article also gives the estimate, without specifying the time, that the UA had 3,000 to 5,000 members. However, he explicitly limits himself to the first UA founded in Düsseldorf in May 1931.

The journal Proletarische Sozialpolitik reported as early as July 1931 that the Düsseldorf Unified Association had „more than 10,000 members“.

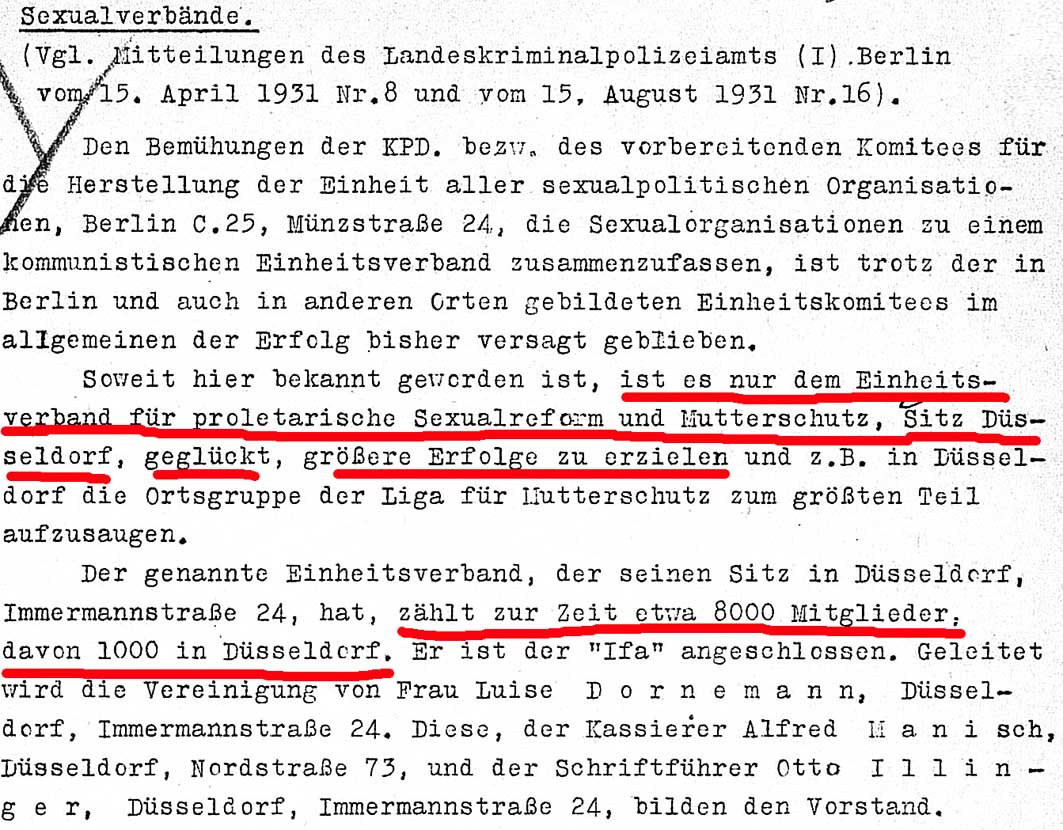

Was this an exaggerated figure for propaganda reasons? If so, the exaggeration was limited. Police files certified on February 15, 1932, that the Düsseldorf UA was the only one of the „sexual associations“ supported by the KPD that had succeeded „in achieving greater successes and, for example, in Düsseldorf, in absorbing the local group of the League for Maternity Protection for the most part.“ It „currently has about 8000 members, 1000 of them in Düsseldorf.“

Police files from February 15, 1932 (Landesarchiv Berlin, R1501/20979, sheet 27)

But the UAs founded later were also evidently successful in recruiting members. On June 28, 1932, the police evaluating a UA conference in the Ruhr region noted: „According to the annual report, the number of members changed from the end of November 1931, when 3055 members were counted in 18 local groups, to 6010 members in 40 local groups on April 15, 1932. In the Ruhr region alone, therefore, there were over 6,000 members in the spring of 1932.“

In the issues of the Warte available to me, I could not find any information on membership figures. However, information on local groups of the UA is given.

In March 1932, 33 local groups are mentioned for the Ruhr area, in July ten for the Lower Rhine region, and in October 22 for Berlin, for a total of 65. But these are not lists of all the local groups, only information about which of them held events, counseling sessions, distributed contraceptives, or the like. In addition, there were further activities at least in the subdistricts of Saxony, the Middle Rhine, and Halle-Merseburg (Die Warte 10/1932, p. 16, 12/1932, p. 14), and thus probably also further local groups.

That it did not remain with the 22 groups also in Berlin, proves a further document: the circular letter of the Berlin UA- District Management from January 1933.

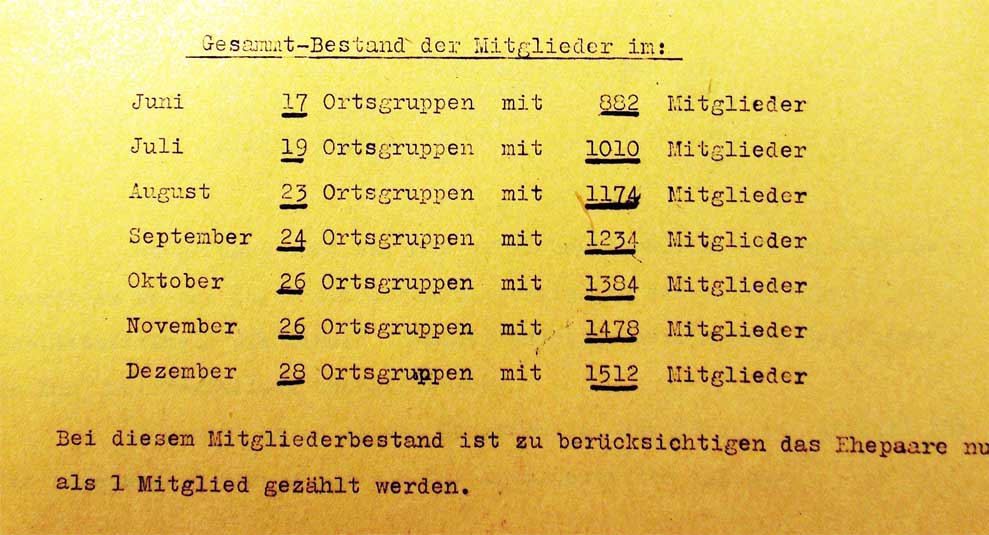

In June 1932 the 17 Berlin local groups have had 882 members. In December, it said, there were already 28 local groups with 1,512 members. This is, especially since „married couples were counted only as 1 member,“ an increase of almost 80 percent in seven months.

From the January 1933 newsletter of the Berlin UA district leadership.

If we add up the available figures, we arrive at a minimum of 8,000 (region around Düsseldorf) plus 6,000 (Ruhr area) plus 1,500 (Berlin) for the end of 1932, i.e., a total of 15,500 EV members secured by documents. Since there were other UAs and membership presumably grew overall, the number for the total UA must have been much higher.

With his determination of a maximum of 3,000 members, Bahnen thus discredited himself.[2] Rackelmann, on the other hand, could be correct in his assumption that there were fewer than 10,000 members in 1931. By the spring of 1932 at the latest, of course, much higher numbers can be assumed.

But Reich already spoke of 40,000 „captured“ members in 1931. Was he exaggerating after all?

No.

I think it is possible that the figures given refer only to individual members and that – in the usual way for KPD mass organizations – „corporate members,“ i.e., other associations, joined the sections of the overall association. The umbrella organizations ARSO and IFA had called on their „memberships,“ which consisted not least of other mass organizations, to cooperate actively. Therefore, if this procedure had also occurred in the UAs, this would have caused the numbers to explode. But to take these numbers seriously would have been pure eyewash.

As a possible reason for Reich not exaggerating in this respect, I think something else, which neither Bahnen nor Rackelmann consider, is far more conclusive: Reich was talking here neither about the original Düsseldorf association nor about the total of all UAs.

Reich states, as already quoted, that the UA founding congress – i.e. the one on 2.5.1931 in Düsseldorf – had „captured about 20,000 members in a total of about eight associations“. The number 20,000 thus clearly does not refer to the Düsseldorf UA itself – which Reich, by the way, usually distinguishes from the other „unified organizations“ as the „West German Association“ – but to the congress organized by it and the members of those eight or so sexual reform associations that participated in it.

According to information in Warte 5/6 1931, p. 7, these apparently included: the Association for Sexual Hygiene and Maternity Protection, from which individual local groups soon transferred to the local UA, as well as the League for Maternity Protection, whose regional fraction this UA was able to „absorb for the most part“ according to a later police report. The League of Conscious Sexual Reformers also joined on 17.5.1931. Since in July 1931 a membership of 21,900 is given for the League for Maternity Protection alone, the delegates assembled on May 2, 1931, may in fact have represented far more than 20,000 members.

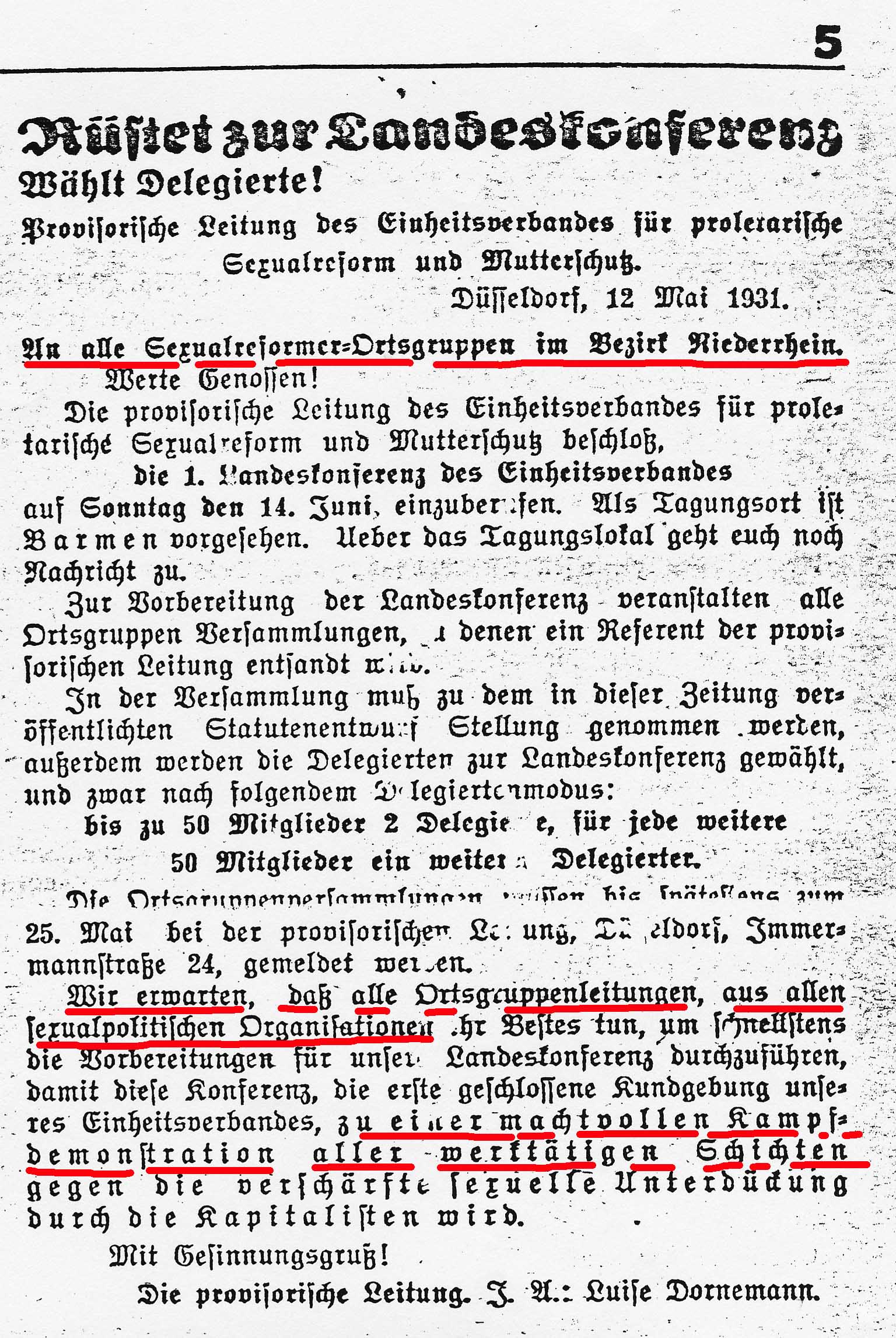

The Düsseldorf UA and its parallel organizations also did not see themselves as self-contained entities, but as a rallying point for all other German sexual reform associations, their local groups or members, insofar as they were willing to join the UA goals. Thus, in preparation for the congress of June 14, 1931, UA secretary Luise Dornemann continued to address „all sexual reform groups in the Lower Rhine district“ and the „local groups from all sexual-political organizations“ (Die Warte 5/6 1931, p. 5).

Die Warte 5/6 1931, detail

To the extent that these other organizations cooperated with the unified associations, information was also provided about their activities.

Moreover, not only through the Warte, but especially through the contraceptive distribution and sex counseling services, as well as the numerous local and regional events offered, far more people were certainly addressed or reached than the total of all UAs had members.

And this, I think, is what Reich must have been referring to when he wrote that „the movement“ had counted 40,000 members within a few months.

He also nowhere claims that the UA allone had this high membership. I think he was never concerned with something as formal as a registered association, but rather with a movement, i.e., with all those people who stood behind the goals represented first by the Düsseldorf and then by the overall association of UAs. The latter, in turn, was for Reich certainly only the provisional shell for the intended unification of all sexual reformers under a sexual-economic program.

Another source might confirm this view: Luise Dornemann reports retrospectively, though without naming a year, that the total of all UAs „covered several tens of thousands of women.“

If one adds the men even in the same number, the order of magnitude given by Reich also results.

So also here is no reason at all to certify Wilhelm Reich that delusional traits are expressed in his figures.

***

Literature

Bahnen, Peter (1986): Massenpsychologie des Faschismus. Entstehungs- und Wirkungsgeschichte der politischen Psychologie Wilhelm Reichs (not published)

Bahnen, Peter (1988): Wilhelm Reich – gegen den Strich gesehen, in Pro Familia Magazin 6/1988, pp.5-8.

Fallend, Karl (1988): Wilhelm Reich in Wien. Psychoanalyse und Politik, Wien/Salzburg: Geyer-Edition.

Clemens Klockner (ed.), Proletarische Sozialpolitik. Organ der Arbeitsgemeinschaft sozialpolitischer Organisationen ARSO 1931 [Reprint, Darmstadt 1987, pp. 169f.]

Rackelmann, Marc (1992): Der Konflikt des ›Reichsverbandes für proletarische Sexualpolitik‹ (Sexpol) mit der KPD Anfang der 30er Jahre, (not published), FU Berlin.

Rackelmann, Marc (1993): Wilhelm Reich und der Einheitsverband für proletarische Sexualreform und Mutterschutz. Was war die Sexpol?, Emotion. Beiträge zum Werk von Wilhelm Reich, vol. 11, Berlin: Volker Knapp-Diederichs-Publikationen, pp. 56-93.

Reich, Wilhelm (Anonymus) (1934f): Geschichte der deutschen Sex-Pol-Bewegung, in ZPPS issue 3/4, pp. 262–269.

Reich, Wilhelm (1995) [1982]: Menschen im Staat, Frankfurt/M.: Stroemfeld/Nexus.

BA (Bundesarchiv) estates NY 4278/1, estate of Luise Dornemann.

Notes

[1] Abridged, slightly changed, illustrated and translated version of Peglau, Andreas (2017): Unpolitische Wissenschaft? Wilhelm Reich und die Psychoanalyse im Nationalsozialismus, pp. 126-133.

Please cite as: Peglau, Andreas (2023): Mass Organization or „small splinter group“? About the German „Sexpol“ (https://andreas-peglau-psychoanalyse.de/mass-organization-or-small-splinter-group-about-the-german-sex-pol/)

As to the sources used in this text, please look at its end.

Please note: My English skills are not very good. Therefore, I first translated the text with DeepL and then corrected it. I expect that there are still translation errors – and ask those who discover such errors to send a message to info@andreas-peglau-psychoanalyse.de

[2] Peter Bahnen cannot be reproached for not delving deeper into the chosen topic in the context of a master thesis – but he can be reproached for the fact that he mostly drew far-reaching wrong conclusions from the much he could not find. His motto seems to have been: Where he could not discover evidence for Reich’s communications, Reich must have lied. In this respect he thus unfortunately joins – despite all valuable research results – the almost throughout sloppy-biased approach of declared opponents of Reich.

The forwarding and distribution of the above text for non-commercial purposes is expressly desired.

Here you can download it as pdf.

Andreas Peglau: Unpolitische Wissenschaft? Wilhelm Reich und die Psychoanalyse im Nationalsozialismus.

With a foreword by Helmut Dahmer and a detailed appendix of documents.

3rd, corrected and expanded edition 2017, Psychosozial-Verlag Gießen. 680 pages, softcover, 49.90 euros.

ISBN 978-3-8379-2637-8

https://www.psychosozial-verlag.de/2637

Also available as e-book:

https://www.psychosozial-verlag.de/7289

Here you can find the book’s table of contents, preface and index of persons. The complete list of sources and references of the book „Unpolitical Science?“ including all sources used in the above text can be read here : https://andreas-peglau-psychoanalyse.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Quellen-und-Literatur-Peglau-Unpolitische-Wissenschaft-Wilhelm-Reich-und-die-Psychoanalyse-im-Nationalsozialismus-Psychosozial-Verlag-Gie%C3%9Fen-2017.pdf.